- Home

- Nigel Flaxton

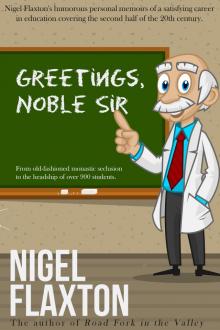

Greetings Noble Sir

Greetings Noble Sir Read online

Title Page

GREETINGS, NOBLE SIR

by

Nigel Flaxton

Publisher Information

Greetings, Noble Sir Published in 2013 by

Andrews UK Limited

www.andrewsuk.com

The right of Nigel Flaxton to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1998

Copyright © 2013 Nigel Flaxton

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Any person who does so may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Introduction

I was fortunate to be born rather late in the twenties and so missed call-up for the Second World War by just one year. When I did register I found that if I wanted to train for teaching I had to apply for deferment, which I did. Call up followed after the two year course, delaying my entry into a permanent post by almost another two years. I finally gave up work in 2006 so I was involved with education in various roles for the entire second half of the twentieth century.

This is an account of some of my experiences with comments upon the considerable changes I saw in teaching and learning over that period. I hope, also, that it conveys something of the enjoyment I experienced during a very satisfying career. To avoid embarrassment, usually my own, I have changed all relevant names. I apologise unreservedly if, in so doing, I have inadvertently selected the name of someone else who was not part of my experience.

NF

Chapter 1

‘GREETINGS, NOBLE SIR!’

The improbable salutation didn’t sound particularly pompous because it was chanted in chorus by forty-six lively ten year olds. What made it so unlikely and added so much to my confusion was that it was directed at me, only seven years their senior. To make matters worse they leapt to their feet to bestow it and embellished it with a kind of salute.

This was the first time I had looked at a class from the front of the room since becoming a student teacher all of three weeks previously. But as I well knew I should certainly not have been at the front; I should have been seated with the other students and a tutor at the back, in safe anonymity.

The class teacher was annoyed, and glared. He was taking a demonstration lesson for our group and was nicely into his stride when my late intrusion disrupted his flow. The tutor turned in my direction from his seat and I flashed what I hoped was an apologetic glance, then nearly collapsed on the spot. He was no ordinary tutor - he was St Andrew’s Training College’s Vice-Principal. I had really put my foot in it!

As I looked round desperately for a seat an unnerving silence settled upon the class and I felt the steam of embarrassment envelop me. Dimly, through hot clouds of confusion, I could see the children’s faces wearing that expectant look characteristic of a group watching from comfortable safety the squirms of an individual in trouble.

I had been stupid enough to be late leaving the College. I knew the school we were to visit was not far and, when I lost sight of other students ahead, thought I knew the way. I took a wrong turning and walked too far. When I back-tracked to St Barnabas Roman Catholic Junior School I was greeted by an empty playground and silent buildings. My heart sank sickeningly.

I hurried through the large green iron gates flanked at the pavement’s edge by the safety crush barrier. As I crossed the playground the metal tips on the heels of my shoes drummed the message of my tardiness loudly and insistently. But the large windows in the red brick walls, divided into many small panes, were set high and mercifully no faces of the inmates could be turned towards me. Thankfully I spotted a pair of solid wooden doors, also painted green. I pushed open one of these, did the same with the heavy brown swing doors immediately inside, which closed with a noisy thump behind me, and found myself at the end of a long empty corridor.

Classrooms were ranged on either side but the doors were firmly closed. I tried peering through the panes of glass in one or two but the view was obscured by notices or pictures strategically placed to discourage unwanted Peeping Toms like me. Once or twice I did gain a glimpse of a class but the children were hard at work and I couldn’t bring myself to disturb the peace by entering and confessing my foolishness to complete strangers. Finally I turned a corner at the end of the corridor and in the distance saw a very tall man walking stealthily with head bent forward. He didn’t see me immediately and I watched him pause by a classroom door. He seemed to be listening and it suddenly dawned on me that he was the Headmaster and was checking for evidence of unruly noise. I considered that singularly unnecessary for, as I knew very well, the place was as quiet as a tomb. He looked up as I walked hesitatingly towards him.

‘Excuse me, Sir,’ I began, then noticing his clerical collar, fumbled for the correct address. I had absolutely no experience of Catholic churches or schools....’er, Reverend Father...’ That came from whence I knew not, but it sounded right.

‘Oh, good afternoon, young man. I had no idea you were there,’ he replied in a pleasant but firm voice with a hint of Irish. ‘What can I do for you?’

‘I’m looking for a group of students,’ I ventured nervously. ‘That is, I should be with a group that were due here this afternoon.’

‘Oh dear,’ he said, rather heavily, ‘you are late, aren’t you? They came some time ago. They’re with your tutor in Mr McCormick’s classroom. Come on, I’ll take you there.’

‘Oh, thank you so much,’ I gasped, relieved the situation was being retrieved at last. I dropped into step with him as he strode down the corridor and across the hall. As we walked I explained why I was late.

‘I don’t like having lessons interrupted,’ he answered, ‘and normally you would have to wait until the end. However, as this is your first visit, I’ll let you go in.’

My heart sank again. Obviously being late here was a particularly odious crime. I knew already the College’s view of such matters because in his first lecture the Vice-Principal had impressed the fact upon us in no uncertain terms.

‘Students must maintain the very good name of the College by being punctual, courteous and industrious at all times when visiting or working in schools.’

As he addressed us in the old lecture room, resplendent in both cap and gown as a deliberately impressive introduction, we decided it would never do to cross this imposing authoritarian figure. Little did I realise that I was about to be ushered into his presence, in front of a class with its teacher and a group of students, extremely late - and by the School’s Headmaster of all people! It was to be a singularly inauspicious beginning to my teaching career.

But I wasn’t actually ushered in. No doubt knowing what was about to happen and feeling it would teach me an appropriate lesson, the Head stopped short of the door.

‘That’s the room. I’ll leave you to go in and make your apologies. But do try to be on time next week now you know how to find us.’

‘Thank you very much, Reverend Father, I certainly will,’ I said, laying it on slightly but no less fervently, then moved to open the door.

The eruption of the class turned the beginning from merely inauspicious to positively ghastly. In the event, Greetings, Noble, and Sir were utterly inappropriate in their attribution to me.

Of course, it was simply the School’s method of extending courtesy to a visitor. However, it w

as accorded to each and every person who went into any classroom - all men were Noble Sirs and all women Gracious Ladies whether they were teachers, caretakers, cleaners, or - very rarely - parents. The exceptions were the Headmaster, and the Headmistress of the attached Infants’ School. These were accorded ‘Greetings and blessings Reverend Father/Mother’. The children were blessed en bloc in reply, but no doubt an individual then hauled out of the room to account or atone for a misdemeanour felt decidedly unblessed.

The classes were large and full of lively personalities bred in the old industrial area surrounding the School. Obviously they enjoyed the chance of enlivening a lesson occasionally by leaping to their feet and chanting their mandatory greeting. No wonder the Head let me enter the room on my own. Later, in a more reflective frame of mind, I realised the custom enshrined not only courtesy but also an effective deterrent to classroom interruptions.

The other students were taken aback as well. However, ensconced as they were on chairs around the sides and rear of the room they soon recovered their composure and with forty-five members of the class enjoyed the completion of my discomfiture when I realised there was no chair waiting for me. But there were two vacant places in the rows of double desks containing the children. One was right at the front and consequently unthinkable but the other, mercifully, was near the back well away from where Major Darnley, the Vice-Principal, was sitting.

Quickly, before anyone could be sent on the errand of fetching a chair from another room, I stammered an apology to Mr McCormick at the blackboard and bolted for the back. The forty-sixth member of the class was the girl sitting in the other half of the desk I had spotted, who became highly embarrassed as I attempted the difficult task of fitting my lanky frame into it. I slid on to the wooden seat easily enough, but had a real problem squeezing my long legs and big feet past the cast iron framework and failed to fit my knees under the spacious book compartment with its heavy lid, which I thumped noisily with my contortions. I finished with legs apart and knees poking upwards, giving a tolerable imitation of a grasshopper. My companion blushed furiously at the giggles of children nearby, for not only was she now perforce sitting by a male, she was also being gradually ejected by my right knee.

Finally the class, accepting the show was over, returned its attention to Mr McCormick and his demonstration lesson. As their gaze swung away from me I tried to lapse into obscurity but failed signally due to my transfixed posture. The slightest move I made to ease my limbs punctuated the salient points of the lesson with loud crashes of the desk lid.

The exercise we were beginning was ‘Instructional Practice’ and we were to look back on it as a particularly helpful element in our training. Obviously the practice of teaching is a fundamental part of all teacher training courses, but frequently students were dispatched to schools and visited only occasionally by their tutors. The less-than-full-year Post Graduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) usually put students into schools for one of the three university terms. whilst the three year Bachelor of Education course, introduced in the late sixties, allows practice to be divided into shorter blocks with a more useful time spread. But inevitably it falls to the individual school to supervise most of the students’ efforts as, rich with inexperience, they face classes for the first time simply because it is impossible for tutors to be assigned to them individually. To-day, also, mature students with other qualifications who want to move from other employment can qualify as teachers largely with on-the-job training. Sensibly they will seek out schools with good track records in such guidance. At best, schools and teachers have always given excellent tutorial support. But at worst the fledglings were dropped in at the deep end and sank or swam according to their personalities. Robust ones always made it. It was unfortunate that in the past the less-than-robust nearly always made it as well. The failure rate was extremely low in the immediate post war years as the child population expanded and more teachers were required despite class sizes that would be regarded as horrendous to-day.

In the past some colleges were dynamically involved with the practical aspects of teaching; St Andrews had possessed its own Practising School on the College site to which tutors and students were regularly assigned as part time teachers. This ceased to function following a direct hit during an air raid so the pupils transferred to neighbouring schools. Instructional Practice was conceived to provide the next best experience for us.

The system involved groups of students each with a tutor visiting schools to take responsibility for lessons of particular classes for half a day each week for a term. After the first demonstration lesson the students each taught lessons in turn. Next day each group held a discussion in College with its tutor to make a critical appraisal and prepare the outline for next week’s lessons. Had the work been too difficult or too easy for the pupils? Did the student hold their interest? Had he done sufficient preparation? Were his instructions clear and precise? How had he dealt with the problem when Mary accidentally spilt glue on Robert’s new shirt? What changes should be made if the lesson were to be repeated? Each week the lessons were examined increasingly microscopically as the term progressed. Obviously a student whose turn came later was expected to learn by the mistakes of those who had taught earlier so they were challenged more robustly. By the end of the exercise lessons were being torn to shreds with reckless abandon as we seized on every minor contretemps - and were stubbornly defended by the embryonic teachers.

Naturally we realised that in the normal routine of day-to-day teaching no lesson is ever subjected to such searching analysis. Even OFSTED team inspections to-day are normally undertaken by one person per class. But the experience certainly made us sensitive to every aspect of planning, presentation, class control, evaluation and later modification. It taught us much and I am sure we all benefitted in later years. Hopefully so did our classes.

As we settled into the routine and got to know one another we decided Instructional Practice at St Barnabas Roman Catholic Junior School needed livening up. We got our chance quite soon when it was Bill Heppleton’s turn to teach.

Bill was a stolid north country lad who, unlike most of his breed, didn’t possess much of a sense of humour. He was ambitious and determined to become a successful teacher, which was most laudable, but he was prepared to accomplish this at the expense of others, which was not. In our critique seminars he did his utmost to impress the VP with his analytical skills by prodding at every minor blemish on the smooth surface of other lessons. The rest of us formed the impression that he intended making his first lesson something really worth watching. We decide to help him achieve this goal.

It was borne in upon us that the budding teacher had to be in the classroom before the pupils arrived. Accordingly Bill stood in front of the empty desks and checked the pile of papers that were the worksheets he had prepared. It was a History lesson and the topic was ‘Monasteries’.

The bell sounded signifying the end of the afternoon break and the children filed in. As was their custom as soon as they were all standing in their places, they began chanting a ‘Hail Mary’. The fact that Mr McCormick was not in the room and that we students came from a College supported by the Church of England mattered not a whit. They always said this prayer on entering the room and, having done so, sat down. Momentarily silent they turned their corporate eye on Bill.

He looked at me rather disconcertedly. I was sitting at the back but the chairs flanking mine were unoccupied. Major Darnley also was absent and I was the sole representative of the student body. I assumed what I hoped was a Poker face and sat back as though I could see nothing unusual. But I knew what Bill did not - that Archie Forton was contriving to waylay the VP and Mr Mac as they emerged from the staffroom where, no doubt, they had enjoyed the traditional cup of tea as yet denied to us students. We were supposed to be far too busy during the half day practice to have time for such luxuries. I also knew where the other students were.

�

�Are you teachin’ us to-day, Sir?’ asked a precocious blonde with ringlets and a pink blouse.

‘Course ‘e is!’ said a tough looking lad with holes in the elbows of his faded brown pullover. ‘ E’s standin’ there, ain’t ‘e?’

Due to its proximity to the College the children were used to having groups of students in their classroom, but it was a rare event to get one on his own and virtually all to themselves.

‘What’s the lesson about, Sir?’ asked another voice.

‘If no one comes in, will you send us out to play again?’ wheedled another.

‘Oo, yes,’ joined in many more, ‘go on, Sir, please...’

Bill was wise enough to realise he was lost unless he acted quickly. Though obviously annoyed at having a minimal audience to appreciate his carefully prepared attention-catching opening, nevertheless he plunged in.

‘No, I shall not. Never mind where the others are. I’m here and I’m taking the lesson. Now sit still, and watch.’

He seized a suitcase from the floor in front of him, placed it carefully on the high teacher’s desk and opened it gradually in true magician’s style with the lid towards the class. Slowly he began to take something out. The children naturally became perfectly silent and watched.

Something long began to emerge, a thick, brown, coarse material. Suddenly, with a flourish, he swept it out fully and held it at arm’s length.

‘There!’ he said triumphantly. ‘Now, if I were dressed in this, what sort of a person do you think I would be?’

‘A monk!’ shouted every voice.

Bill looked surprised. He had forgotten the possibility of Catholic children being used to seeing monks’ habits.

‘You’d ‘ave to ‘ave the top o’ your ‘ead shaved,’ called out a cheeky but angelic faced lad in the front row who had already troubled two or three of us with disconcerting questions and comments.

Moltation

Moltation Greetings Noble Sir

Greetings Noble Sir