- Home

- Nigel Flaxton

Greetings Noble Sir Page 2

Greetings Noble Sir Read online

Page 2

‘Would you like that, Sir?’ asked someone else.

‘Be quiet,’ snapped Bill. ‘Now listen. Yes, this is the dress of a monk. Now where do monks usually live?’

Before the assembled company could boom the next obvious answer, Gordon Mersely opened the door.

‘GREETINGS, NOBLE SIR!’ chanted the class dutifully, standing up with a great clatter as the heavy desk seats crashed back on the iron frames. Gordon nodded at Bill.

‘I do apologise, Mr Heppleton,’ he said. He rapidly turned away and made for his chair. When he sat the children did likewise, again to the staccato rattle of seats.

From the front Bill watched open mouthed, having been stopped so abruptly. With an effort he collected himself then turned his gaze heavily from Gordon to the class.

‘Well, I’m sure you all know that monks live in monasteries,’ he said, sensibly scrapping his question. ‘Now, you will all need one of the sheets of paper I’ve duplicated.’ He pointed to one pupil in each of the four front desks. ‘One, two, three, four - you take these and give them to everyone in your row.’ Four piles of proffered sheets were grabbed by the recipients with slightly overdone enthusiasm.

At this point I nodded at Trevor Walfrey who was peering surreptitiously through the door window, just as Gordon had done a few moments earlier. Trevor made his entrance with a commendable flourish.

‘GREETINGS...’ chorused the class to the familiar noisy accompaniment. Trevor didn’t look at Bill as Gordon had done. Instead he strode to his chair wearing a fixed expression and stared intently at the worksheet of the pupil sitting in front of him. I could see the corners of his mouth twitching.

So was Bill. With three students in and seven to go, realisation hit him hard. He was furious. He strode to the door and flung it open. He glared up and down the corridor outside but it was completely empty. We guessed he might do this at some point and had decided the group would wait beyond a corner and that each next entrant would only move up to the door when he guessed the lesson was proceeding. That particular spot also put the conspirators in a better position to hear the approach of the VP and Mr Mac when Archie’s list of questions about his forthcoming lesson became exhausted, or they brushed him aside and made for the classroom. In that event the group judged they could manage a combined dash and entry that would be tolerably spectacular.

Bill slammed the door in annoyance. The class watched with mild interest and waited for him to continue. They hadn’t twigged yet.

But they got it when Malcolm Ashterleigh entered in similar fashion. The buzz went round as they leapt to their feet and fairly shouted their greetings at him. As he sat down some turned and took stock, pointing to our seats. Four in, six to come! If only Mr McCormick and the other old chap stayed out, their afternoon was made.

But Bill’s certainly wasn’t. Attention was riveted on the door and he fought to retrieve it.

‘Never mind these interruptions, children,’ he said tersely. ‘Look at the sheet. I’ve drawn two pictures of monastery buildings and at the side there is a list of names of the rooms. I want you to write each name on the picture where you think it should go. Let’s think about the first one...dormitory...’

‘GREETINGS NOBLE SIR!’ yelled the class at Berny Wilton.

‘Oh, do come in, Mr Wilton,’ Bill tried heavily. ‘So glad you could join us.’

The class enjoyed the irony. They were with us wholeheartedly; positively glowing with mounting excitement. What a fun afternoon!

We managed two more. After Berny’s entrance Bill did the only possible thing. Having told the class what to do he retired to the teacher’s desk and waited for them to finish the work. The class, pencils poised, watched the door.

After Jon Kennton and Bob Brinkton made successful home runs Archie’s ingenuity faded and with the VP and Mr Mac he walked heavily along the corridor. The last two picked up the sound of footsteps and provided the class with a grand finale as they burst in and sat down hurriedly. Bill guessed from their haste the show was over. He rose heavily to his feet.

‘Now perhaps we can get down to work,’ he admonished. ‘Just finish off that first section of the sheet.’

But there was one more entrance to be made and when it came the children overdid things. There was just too much excitement about their greetings to Archie and the two men and it was accompanied by some giggling that almost gave the game away.

‘There’s no need to shout so loudly, we are not deaf!’ said Mr McCormick sharply. He turned to Bill. ‘I’m so sorry for this interruption. We were delayed. I hope we haven’t spoilt your lesson.’

I thought Bill was going to have apoplexy. The class, on the other hand, having had a thoroughly satisfying ten minutes of pure entertainment turned their attention quite willingly to monasteries. But a few contrived to flash delightfully conspiratorial glances in our direction.

Dame Fortune does her best to redress the balance of life when possible and I was the recipient of her ministrations on Bill’s behalf. At the seminar next morning, when his lesson was to be discussed, the VP surveyed us closely.

‘Gentlemen, I missed the beginning of Mr Heppleton’s lesson yesterday because I was discussing next week’s work with Mr Forton. Would someone be good enough to tell me the relevant points of the lesson prior to my coming in? Do you feel the beginning was sufficiently lively to secure the children’s attention?’

The rest managed to keep their mirth silent but involuntarily I chortled aloud, which left me facing the VP’s sharply questioning stare alone. I also had to deal with the problem of explaining what I found amusing about the production of a monk’s habit from a suitcase. I failed miserably, to Bill’s delight. He deserved no less. But the VP’s scowl proclaimed eloquently his view of me as a shallow character unlikely to take teaching seriously. I had got firmly on the wrong side of him twice in the space of my first few weeks in College.

It was not at all the kind of beginning I had imagined for myself.

Chapter 2

The College had been built in a pleasant pastoral setting in the middle of the nineteenth century when the need to expand elementary education was being accepted by various religious organisations. It was twenty years old when Forster’s Education Act decreed compulsory education for all and ninety years old when the Midland city in which it stood was regularly bombed. Its site was not far from the centre, in twentieth century terms, and for years it had stood cheek by jowl with factories whose wartime production made them worthwhile targets. A number of bombs exploded harmlessly within its perimeter walls, excavating craters in its lawns and cricket field but these did not immediately interrupt the flow of its life. Young men continued to pass through it during the early war years, emerging to go directly into the Armed Forces. Then a direct hit on one of its wings caused a rapid and complete evacuation.

For the remainder of the Second World War its life was completely uneventful. The buildings were unoccupied except the refectory and kitchen which became a ‘British Restaurant’ for the local populace. These institutions were government sponsored, locally organised replacements for many local cafés Closed for the Duration as the familiar notices announced. Meals were basic but reasonably wholesome. They were a godsend to those families bereft of hearth and home in the sudden night.

In 1945 the College was rapidly reopened to cope with the large wave of students needed for the forthcoming bulge in the child population. With rapid demobilisation of men from the Armed Forces that piece of planning needed no prior investigation into anticipated changes in social activity. Existing facilities had to suffice; there was no time or money to extend buildings or refurbish rooms beyond the necessary minimum to get the production line working again. Every possible room was pressed into service to contain beds.

Training College courses were two years in length. Such was the urgent need for teachers that an Em

ergency Training Scheme was set up, providing a mere one year course for selected men and women returning from the Forces. Across the Country a scattering of empty buildings of widely varied quality was pressed into service as Emergency Colleges which operated until well into the fifties. Typically the scheme provided fertile ground for seeds of class distinction in the education service; years later ‘Emergency Men/Women’ found promotion harder to come by unless they gained further qualifications. Nevertheless selection was rather more strict than for normal courses; Hansard records an answer given in 1948 by Mr Tomlinson, the Minister for Education, that following a new recruitment drive, of 11,200 women who applied 6,800 had been rejected or had withdrawn; 2,650 had been accepted whilst 1,750 were being processed.

The Reverend D.W.Silton MA (Cantab.) was Principal of St Andrews. He was an ageing bachelor whose life had been devoted to training students. He had been in post for virtually all the years between the wars and thus experienced the turmoil of the second towards the end of his career. The immediate aftermath was an even greater upheaval for him - quite literally. He relinquished the spacious Principal’s house in the College grounds, filled most of its rooms with beds to accommodate even more students, and occupied a single room next to his study in College as a bed sitter. He knew it would be for two years at most. He knew changes were on the way and he wanted none of them. He would be happy to retire once the old place was back in business.

So it happened that I entered the College at a time when the past was still with it but the future was about to descend in true whirlwind fashion. I don’t think any of us realised we were to receive a pre-war training for post-war schools. Looking back, on the whole I am grateful this was so, for whilst my teaching experience spanned much of the second half of the century and embraced many changes in education, nevertheless I felt firm on the bedrock of old-fashioned training. I found that especially useful because my nature is to look ahead most of the time and welcome change. Occasionally, though, my roots provided the strength to remain firmly planted when buffeting winds swirled without direction.

I failed Latin at School. I was in an Arts Sixth Form of eight students, four in each year. Few teachers could be spared to teach such small groups - the Science side faired better, mustering about twenty-five in each year. The whole Sixth Form totalled just under sixty students in a Grammar School of six hundred; a ten per cent ratio that was quite normal at the time. In a forty period week I was taught for only seventeen and even some of these were shared between Upper and Lower Sixth. I had not taken Latin in the lower forms, then found I needed it for university. Course advice was non-existent. I tried to take the subject from scratch with minimal teaching but didn’t make it.

The fact that I discovered girls at the same time no doubt contributed to my failure. This happy state was surprisingly enhanced at school in a totally unexpected quarter. Many unlikely teachers were called upon to fill gaps caused by those who had been called up, making teaching standards a patchwork quilt. Youth, inevitably, was singularly lacking in the wartime profession. Call up for military service began at the age of seventeen and a half. Compulsory registration for Service actually reached the age of forty-one and many approaching this age were taken. But near the end of the war the call-up of young women was eased; then female teachers of tender years were sometimes employed to fill the gaps in schools for boys.

Six months before higher examinations I found myself, at sixteen plus though growing rapidly, with a most attractive though diminutive twenty-one year old mistress - the teaching sort, that is. During the sunny spring and early summer prior to my examinations we found a pleasant spot amongst the roof gables of the old building which conveniently could be reached via the fire escape. It was an excellent place for sunbathing, being completely sheltered from both wind and prying eyes. If I pleased her in any way it certainly was not with my prowess at Latin. Neither did I tell her of the Headmaster’s weird obsession that boys and girls should not meet in any way before they reached twenty-one and had concluded their studies, nor how I had discovered the fact!

Quite rightly university places at the end of the war were being made readily available to ex-servicemen and, young though I was, I could not wait another year to retake Latin so I settled for the Head’s offer to ask the Principal of St Andrew’s to consider me for a place at the last moment.

Thus I arrived for my interview in late August. It was also set, quite literally, late in the day, 8.00 pm in fact. I found that interviews continued at half hour intervals until 9.00 pm each day as they considered extra applicants. Dusk was falling and so was steady rain.

I approached the Victorian gothic façade with a truly sick feeling. I had always wanted to teach; only I knew how much. I had missed university but could alleviate my sense of failure by promising myself an external degree later. Teaching was my goal; I would accept anything which led to that - but what could I do if I were turned down now?

The old blue-grey pavement bricks echoed to my footsteps. Small and patterned, each had two rows of raised knobbles and the lines formed between them produced radiating patterns like stars. These collected and held the rainwater, so that as I walked towards each street gaslight I trod a stellar pathway beckoning me onwards. Though fascinated I could only wonder whether the return journey would be so inviting.

The building straddled the end of the road with its deserted pavements. Tall and narrow windows, grouped in pairs, extended in three orderly rows across the entire front with the exception of the middle section which housed a pair of massive, black doors. These arched away to a point; I imagined times when they must have opened to students of yore arriving in horse-drawn coaches, with luggage and boxes piled on the outside, perhaps with the less wealthy ones sitting there also.

As I reached these solid barriers, firmly shut, I felt a momentary twinge of panic as I envisaged having to knock to gain admittance. My fist would have produced the lightest of taps upon their vast structure. I was relieved to see a small pedestrian door let into the framework of the right hand one. I saw no bell, push or pull, but found it opened to my hesitant touch. I stepped through into a short, lofty passage that opened on to a quadrangle.

This area looked most unprepossessing, especially in the subdued light, and consisted of a very ordinary hexagonal lawn surrounded by worn paving stones. It was the centre of the oldest part of the College and I learnt subsequently was known universally as ‘god’s acre’. The absence of the capital was to avoid any possible confusion with the Deity. This was important because the individual I now approached through a small door on my right labelled ‘Enquiries’ was, in fact, ‘god’. His official title was Caretaker but that was rarely used.

The unofficial nomenclature asserted his standing in the hierarchy as far as students were concerned. Generations of students returning after lock-up bestowed the title on this College servant who held power over them by reporting them to tutors, or otherwise. Probably he benefited from ‘otherwise’. But at that moment I knew nothing of this and merely followed the slight figure walking with a noticeable limp across the quad towards the Principal’s study.

This, also, was redolent of age. A large oak desk with inlaid green leather was flanked by two massive bookcases. There were two or three upright chairs, upholstered in leather, and two very large easy chairs similarly covered. I was surprised and confused to be motioned to one of these by the Principal; even more so when I sank into it and had to extend my legs out in front to retain any semblance of an upright posture. No one else was present and I saw only one other person after ‘god’ during this visit. He was another candidate who took my place in the Principal’s study as I left. The place looked and vaguely smelt like a mausoleum.

I was forced to look up to the gowned figure of the Rev. Silton sitting behind the desk. He was tall and large boned, features lined with age, sharp eyes beneath grey bushy eyebrows. From his wide, firm mouth I expected a strident v

oice and swift, incisive questions. Instead I was surprised to hear a fairly quiet, almost apologetic voice asking me trivia. In the flush of youth I never considered the probability he was tired. Later I was to see the rigid authoritarianism he still practised in the College which belonged to an age soon destined to seem a hundred years away. But his last question was the one that left me groping.

‘It’s the obvious one,’ he said diffidently, ‘but it has to be put. Why do you want to teach?’

My mind flashed over my decision which had crystallised in an instant I could well remember. But the process leading to that moment had extended for many years. I knew that, despite my immaturity.

I remembered being a thoroughly bewildered young boy attending my Grammar School for the first time on Wednesday, August 30th 1939. I remembered joining all the other boys in the School two days later, September 1st, as we arrived each carrying one suitcase, a gas mask and one day’s supply of sandwiches, as officially instructed. We were ushered on to waiting buses and taken to the central railway station where we joined many hundreds more youngsters in subdued queues, also being evacuated. We left home with absolutely no idea where we were going; later we found that the teachers were similarly mystified. Only Heads held that information, in sealed envelopes they were forbidden to open until their train journeys began. Society was suffering paranoia about spies. The mind boggles at the notion of some clever interloper collecting the vast timetable and journey information of the nation’s schoolchildren that day, carefully encoding it and transmitting it to the enemy. I also remembered feeling very lonely in deepest Gloucestershire on Sunday 3rd September when I heard that war was declared.

But the sudden and massive bombing feared by many adults from the scenes of the Spanish Civil War three years earlier did not materialise. A schoolboy cousin and I found time lying on our hands. Our School shared accommodation with another, so we had afternoon lessons only, from 1.00 to 5.00 pm six days a week. As the rich autumn gave way to a biting hard winter we turned to imaginative games. He criss-crossed the gentle hills and tranquil lanes of our lengthy walks with the routes of imaginary buses which we ‘drove’ and for which he produced detailed timetables. Indoors he assisted me in organising our imaginary school for which I produced timetables of a different kind, but no less detailed. When we left school he went into the city’s Transport Department and I wanted to teach.

Moltation

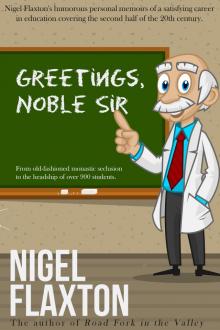

Moltation Greetings Noble Sir

Greetings Noble Sir