- Home

- Nigel Flaxton

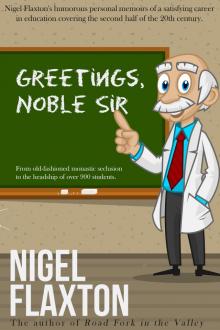

Greetings Noble Sir Page 5

Greetings Noble Sir Read online

Page 5

The only women who ever appeared within the walls were cleaners and refectory servers whose minimum age of employment seemed to be sixty, or thereabouts. Whenever we managed to escape, especially at weekends, we found a few girls of far more tender years lying in wait for us beyond the College gates. We were sufficiently on the ball to know they were tender only in years, so generally these were left alone. The internal College view of them approached the mediaeval view of hell.

We decided we would invite students of a women’s Physical Training College some eight miles away. The only possible room to use was the Students’ Common Room, a bleak affair furnished with heavy round oak tables and similar wooden upright backed chairs. It was rarely used, except during the compulsory evening study period. There wasn’t an easy chair or a cushion in sight. Nevertheless we felt we could liven it up with some decorations borrowed from our homes - new ones were a rarity during the extensive post war years of austerity.

Berny Wilton volunteered to request the Principal’s permission for us to invite guests into the College.

‘To a Dance?’ The Reverend Silton seemed bemused by the notion, as though he had never before faced such a question. ‘I suppose I have no objection to such a thing, if that is what you men want. I am sure I can rely upon you to bring colleagues of good reputation.’

Berny blinked. ‘Colleagues’ seemed somewhat out of context applied to dancing partners, because he hadn’t yet mentioned our intended source of supply. He felt he had to leave no room for error.

‘I am sure all of us will be most careful in that respect, Sir,’ he said. ‘Some men have their own girlfriends for whom they can vouch, but in the main we intend inviting ladies from the PT College at....’

The Principal exploded.

‘Girls? Do you seriously imagine...?’ He glared furiously at Berny. Mr Wilton, you men may have an end of term function if you wish and that function may include dancing if that is an activity in which you wish to indulge with one another. You may bring guests, as well, if you wish. But women they may not be! Unquestionably NOT!’

His retirement at the end of our first year was opportune and effectively marked the end of an era for the College. It had lasted for nearly a hundred years.

Chapter 5

We knew from the brief Prospectus that we were to study Psychology throughout the course as an integral part of ‘The Principles and Practice of Teaching’ but few of us had more than the haziest idea of what it entailed. Nothing so exotic had appeared on our school timetables and I felt a twinge of anticipation at the thought of embarking upon real job-related study. To be honest I knew I could swank a bit about it amongst my other friends. But there was also a touch of apprehension because I had no idea whether I would be able to cope with the unknown. The opening sentence of the VP’s first lecture in the subject confirmed my fear.

‘Gentlemen, we shall study the Paidocentric Theory of Learning during this first term,’ he announced.

‘What the hell’s that?’ breathed Bill Heppleton, next to me.

I whispered back disparagingly, ‘Sounds Greek to me!’

Obligingly the VP concurred. ‘The word comes from the Greek, paidos, a boy. The boy is at the centre of the learning process...’

Bill stared at me, momentarily dumbstruck at my erudition, but when my eyebrows shot up in surprise he twigged I was as clueless as he. The incident lodged in my memory but I’ve never heard the theory glorified by that grandiose title since. Child-centred learning is much more recognisable.

Regrettably writers of courses and reference books have too often clothed their work in unfamiliar garments. The reason probably lies in the mistaken notion that more weight attaches to complex language. Perhaps this arises from the definition of a profession as a group of people that use language and have knowledge not easily accessible to the man in the street. Lawyers, doctors and vets qualify under this heading and we ordinary folk wait upon them to avail ourselves of their specialist services. Recently I heard a dermatologist identify a condition which needed treatment as prurigo nodularis. ‘Itchy lumps’ is a fair translation. But generally in recent years specialists have become easier to understand. We can also find explanations via the Internet

But there are others. In the information technology revolution the term becoming computer literate meant more than just learning how to use software. A baggage of terms needed to be unpacked. How many of us frowned uncomprehendingly when first faced with protocols and portals, drivers and domains, RAMS and ROMS and many more terms deployed by the writers of programs as the PC became a household as well as a business tool? User-friendly courses were greatly applauded.

Whoever conceived the title ‘paidocentric’ was guilty of using an unnecessarily strange term, or obfuscation; as well as being politically incorrect. He ignored girls.

‘The child learns only through experience...’ continued the VP. ‘He can only be conscious of his surroundings by experiencing them through use of one or more of his senses. His surroundings also can be shown to impinge upon his consciousness, thus there is a two way process in operation.’ He broke off to chalk up a diagram showing a circle (the child) with an arrow proceeding outwards, opposed by another arrow charging towards it. They seemed about to meet head on.

‘However, life is not that simple, gentlemen. In reality there are many and continuous interactions between the child and his or her surroundings, which can be conceived as a series of sensations coming in from the environment and being reacted upon.’ He embellished the diagram by making the line continuous with a series of little arrow heads going in both directions.

‘More accurately, the model should be thus...’ He drew concentric circles with arrows flying from all points of the outer stockade towards the beleaguered child in the centre who, to do him (or her) justice, was valiantly trying to repulse one and all with a set of his (or her) own. This image sometimes floats before me when I watch a game show on TV requiring the contestant to parry balls flying at him/her from various directions. Or goalkeepers under training.

‘Now, gentlemen, we come to the key issue. The child, as I said, can only learn from these interactions, these experiences. But many of these are fleeting - a glance, a smell, the brush of a hand, a taste. If repeated often enough the experience will be remembered. However, some interactions are much stronger and the learning is more immediate and long lasting...’

He stopped in mid sentence and stared at us challengingly.

‘These...’ he intoned dramatically, palpably holding one in his cupped and outstretched palm, ‘...are significant experiences...’

He dropped his arms, stood back erect, still as a statue. His blue eyes magnified by his spectacles flashed as he flicked them around catching many of ours individually. We hadn’t a clue where he was leading us.

Then we got it.

‘Each and every one of your lessons,’ his tone assumed a Churchillian timbre, ‘here in practice, out there in your future schools, day in day out, throughout your entire careers, must be significant experiences for your pupils! Nothing less will suffice. That, and that alone, must be your goal. It must be your lifelong touchstone as St Andrew’s men.’

We began to realise that teaching practice was not going to be a doddle. Like everyone else my experience of lessons at junior (then called elementary) school was of a teacher explaining, followed by questions, followed by some form of written work. The pattern was the same for English, Arithmetic, Geography, and History; occasionally Nature Study lessons used specimens - I remember taking an apple for the purpose whilst in the Infants’ School and not eating it beforehand; Art was paint-a-picture-a-lesson, whilst Music was either singing or the use of percussion instruments - I was permanently allotted a triangle. Only at Grammar School in Science did I experience practical investigation. Woodwork we took in the first year; my Mother used the teapot stand for ages for it

was quality oak (dream on to-day’s technology teachers!), but the subject was deemed insufficiently serious for the remainder of the curriculum.

Dredging my memory I wonder how many lessons were significant experiences for me? In fact I can recall some quite clearly - and the common factor in each is the personality of the teacher involved. Palmerston, the 19th century Prime Minister, has the veneer of a tall, thin, sandy-bearded history teacher who described him as ‘a bit of a lad’ and revelled in telling us about dispatching gunboats whenever a Brit abroad was treated badly. ‘Civis Britannicus sum!’ Ah, those were the days.

Then there was an urbane English teacher of solid proportions who really made Shakespeare live for me - he did pretty well with Chaucer as well. He seemed to excel as Antony; Richard Burton later filled the role well but somehow never quite supplanted this man for me.

Perhaps you share such memories? Certainly the personality and enthusiasm of teachers are the sine qua non in the work of schools, but no one can rely on histrionic ability alone for lesson after lesson. Inevitably fatigue sets in for both teacher and student. Finding the supporting interest for lessons is the perpetual challenge, as the VP emphasised to us right at the outset - hence Bill Heppleton’s romp with a monk’s habit. Like him we often misjudged what would or would not capture the children’s interest; the failures provided useful ammunition for our shots as hapless targets stood in the firing line for the subsequent critical appraisals. On our longer practices we fired at ourselves in the follow-up notes we had to write on two lessons each day.

As the first year of our training progressed we drew nearer to the first period of block practice. For this we were to be allocated to particular schools, usually individually though some were large enough to swallow a pair of students without too much damage to children’s lessons. During the month’s practice we attended throughout each day, returning to College each evening to prepare lessons for the following day. Each of us was assigned to a class teacher whose job it was to let his or her class fall gradually into our awkward and unskilled hands and prevent us from making too much of a hash of things.

The College, for its part, assigned all its lecturers as tutors to the schools on a group basis, one tutor being responsible for about ten students. They then divided their work between travelling around supervising us and continuing to lecture at College to the senior year.

All our studies in the first year were for the junior age range, youngsters aged from seven to eleven years. Our first spell of block practice, therefore, was in schools for that age band. But schools vary considerably - a fact well known to parents and certainly students. There were good schools and bad schools and all sorts between; and there were all sorts of opinions and rumours and counter rumours....

‘That one’s awful; the Old Man won’t even allow students in the staff room.’

‘God help anyone who gets landed with that place - the building hasn’t been touched since it was built and it says 1870 over the front door!’

‘That’s a beaut. Super new place, finished in 1939, right on the edge of town in a really gen suburb.’

‘If you play your cards right in that place, pal, you’re in. Most of the staff are women and there’s none over thirty. Mind you the Old Man and the Chief Ass. share ‘em most of the time.’

The junior year gradually became desperate for information as the time for block practice drew near and the senior year, with no one to contradict them, were very willing to minister to our needs and gloat as we writhed. The need to land a good school, it seemed, was absolutely vital to us if we were to hold out any hope of a reasonable mark in practical teaching. I quite believe that as the day drew near for the list of our practice schools to be published, St Andrew’s saw an above average weight of prayers being offered up and that the subject of good schools figured amongst them to an excessive degree.

In the meantime we were given instructions in various teaching techniques and shown how to prepare lesson notes in the minutest detail. We soon realised that when the tutors were visiting our schools they would put us under the very closest scrutiny.

Our lesson note books, it seemed, had to be models of neatness and presentation because they were to be available in the classrooms at all times for our own and everyone else’s use. We were adjured to write only on the right hand pages leaving the left hand ones entirely free for the advice to be poured upon us by class teachers, tutors, heads, or even it was whispered in awestruck tones, by His Majesty’s Inspectors. This also provided us the opportunity, they said, to rewrite those parts of our lessons that had not been successful so we would avoid similar pitfalls in the future. Afterwards the notebooks were to be submitted for final marking.

As we very well knew from our half-day-a-week practice, lessons had shape. Each began with an introduction, continued with development and, wonder of wonders, finished with a conclusion. But lessons were given in response to problems which had to be identified first and written about; they also produced results which had to be commented upon afterwards. There also had to be a blackboard summary; this was supposed to show, approximately to scale, the board with exactly whatever would be on the real one at the end of the lesson - words, diagrams and drawings, all in the correct colours if you were going to be that adventurous.

We realised with awful finality that, no matter what our lessons were actually like in the classrooms, our lesson notebooks would have to be masterpieces. So much toil, tears and sweat were put into them that I have never been man enough to throw mine away. Perhaps some archivist in the year 2200 will ponder the problem of the wealth of extant lesson notes from the first half of the twentieth century’s educational system, because I’m sure generations of St Andrew’s and other ex-students have willed theirs to their descendants in perpetuity.

The wags were quick to poke fun at the rigmarole of lesson plans.

‘How the hell do you write the problem for a lesson on writing a letter? asked Trevor Walfrey during an evening study period.

‘Simple,’ said Gordon Mersely. ‘At present the pupils cannot write adequate letters, therefore it is necessary to teach them basic format and content.’

‘Don’t be wet,’ said Trevor. ‘The March Hare will want a hell of a lot more than that.’

The March Hare was the Senior English Lecturer, so called because he had rather prominent front teeth. He also had the mannerism, when inviting you to consider a point, of putting his lower lip under them and gazing at you with his soft brown eyes, raising his eyebrows and murmuring ‘Hmm?’ The ‘March’ bit was a deliberate touch of incongruity because he was elderly and very staid.

‘Alright, how about this?’ countered Gordon. “It has been discovered that these pupils have inadequate knowledge of accepted methods of setting out and modes of style in writing a variety of letters, such as applications for employment, complaints to Members of Parliament and pleas to income tax inspectors; therefore it is necessary to impart these skills.”

‘Super,’ said Trevor, ‘but you went too fast. I didn’t get beyond methods of setting out. What was next?’

‘Rot,’ yelled Gordon. ‘What I said first was plain English. Put that.’

‘Ah, but you don’t get marks for being direct and simple,’ put in Berny Wilton. ‘You have to be more subtle, use a bit of psychology jargon, to show you’re on the ball.’

‘True,’ said Archie Forton. ‘Take Results for instance. If you have a flaming disaster, as I’m likely to, you can’t write, This lesson finished with thirty pupils jumping through the windows, ten having a fight on the floor whilst the remainder were more acrobatic and swung from the lights.’

‘No, but if you gloss over what exactly happened,‘ suggested Malcolm Ashterleigh, ‘it does give you a chance to spread yourself rewriting the thing. That’s bound to impress the powers-that-be.’

‘Well, that’s probably true up to a point

, but you could overdo it,’ said Berny. ‘My bet is that you have to make just the right amount of rehash - you know, enough to show them you can improve on parts that went wrong but not too much because that suggests your lessons weren’t much good in the first place.’

Archie looked thoughtful. ‘This is going to be worse than I thought. If you’re right we have to be damn cunning writing these notes.’

Sociologists would say, wrapped up in a little jargon, that we were producing a classic response to a social situation where one group organises a modus operandi designed to have value for a second group, but the latter responds deviously because the former wields power over it. The format of our lesson notes was laid down by our tutors to help us teach good lessons, but because they marked our books and our performances we tried to work the system to our advantage.

I am sure none of us analysed our actions at the time, but no doubt in our separate careers we all came to know what it was like when the boot was on the other foot. In my case I was on the receiving end in the early seventies when I was giving a series of lessons on education itself as part of a Humanities course. Our pupils visited a number of schools of widely differing kinds; one was Harrow, conveniently arranged through the friendship of one of its staff with one of ours. Another was a so-called ‘Free School’, one of the experiments of the time, usually founded in the most neglected urban areas. Many people regarded both staff and children as drop-outs. Many years later the term has reappeared as the official designation of schools created by completely independent groups.

Because the one we met was very small, twenty-five on roll, and operated in a tiny old church hall awaiting demolition, we invited them to visit us instead. Certainly they had very different social values from our own, amongst which was total opposition to any form of coercion or conformity. In order to let our pupils experience the difference, those from the Free School were asked to act exactly as they did in their own building. Probably they would have done so in any case - but we made the point when making the prior arrangements.

Moltation

Moltation Greetings Noble Sir

Greetings Noble Sir